This is an interview of Jim Douglass, author of JFK and the Unspeakable, by Brayton Shanley that I transcribed this weekend.

Brayton: Jim, you have been inspired to live a life of non-violence; be a disciple of non-violence. How did that happen in your life? What were the major influences let’s say?

Jim Douglass: I think it happened because… when I wanted to be a nuclear physicist I realized that I was not only totally incompetent, but that all kinds of questions were around me and I couldn’t answer them. And I just realized I was in darkness and I left the campus where I was studying, told my parents I was giving up my scholarships, and I joined the United States Army at a time when I would otherwise have been drafted and I couldn’t get back into school because it was between semesters in the nineteen-fifties. In other words I just went in a direction that seems paradoxical because I joined the Army. That opened me to a totally new life than the already determined one in relation to the influences of my parents, my schooling and my background and from that point on I decided I would just open myself to God’s will and to whatever I could learn without any decision as to what I was going to do - be a nuclear physicist, be a lawyer. That’s not the point whether you’re called to be. And I especially wanted to have after twelve years of schooling, grade school, and high school, and Catholic school I wanted to finally learn what it meant to be a Catholic Christian and a follower of Jesus and I didn’t know… That was the basic point of turning and all the rest, such as meeting Dorothy Day, and beginning to read the Catholic Worker and write for it, that all came out of the basic decision to be open rather than to think I knew what I was doing.

Brayton: And then there was the turning point when you were teaching in Hawaii?

Jim Douglass: Yes, that’s the second turning point when I was teaching a course on the Theology of peace. Dr. King was assassinated April 4, 1968. Some of my students without my knowledge burned their draft cards, submitted themselves to years in prison, some of which they served, and began the Hawaii resistance. They asked if I’d like to join them. In a way as though they were very non-violent about it saying put up or shut up Mr. Professor-of-non-violence. And I did join their group and went to jail with them and that was the beginning of the end of my academic career but a baptism into non-violence as a way of life. So through my students and especially through Dr. King I had to go a new way and that also in a long, longer experiment in truth meant understanding Dr. King’s martyrdom as my way to life.

Brayton: And you continued to connect this with faith this idea of non-violence and faith and Jesus.

Jim Douglass: Well, Jesus’ teaching was primary for me and the faith has been liberated for my by realizing after some study and reflection that as I see it the greatest follower of Jesus was not a Christian he was a Hindu, Mohandas Gandhi. So to understand non-violence I haven’t gone so much to doctrinal formulations which are ‘okay’ but to the way, of course the way of Jesus and in our own context the way of Gandhi, the way of Dr. King, the way of Dorothy Day, and Gandhi in particular because I think he more than any other person I’ve encountered just as Jesus was put flesh into the non-violence of God I think Gandhi in his experiments in truth taught us a method, a way of living the gospel and so he’s not only for me the greatest exemplar but also the greatest theologian of non-violence. And truth is God just as Gandhi said and if we go deep enough into the truth we’re going into the presence and transforming power of God.

Brayton: Now you gave a lot of your life and time to work in opposition to nuclear weapons. What inspired you to go there? Why that?

Jim Douglass: When I was a freshman at Santa Clara University a very great teacher whom I had for one semester, Herbert Burgh, introduced our class simultaneously to Dorothy Day, the Catholic Worker, the threat of the total destruction of the world by nuclear weapons, and the meaning of the gospel through the non-violence of Jesus. That was a pretty big integration. So my understanding of non-violence initially is simultaneous with my recollection that we were and are living in a time when it all can be all that we see around us can be annihilated by the evil that we have invented and put out there. I can’t do one without the other. I can’t go around saying I’m a non-violent guy without going to the question and the threat and the dark horror the clout of nuclear weapons, it’s the same thing, you can’t do one without the other. To this day I believe if we want to be non-violent, and we must be, we need to respond to nuclear war and to all the other different dimensions of peace and justice that are related to it but we cannot ignore that one and on the other hand we also have to recognize that Dr. King’s prophesy and Jesus’ prophesy which lies behind it that non-violence or non-existence is not… it’s better to be non-violent and that would be helpful. It’s non-violence or non-existence.

Brayton: So you have a history here. It very much starts in the sixties with Vietnam and then goes into the question of nuclear weapons. You write some books on non-violent cross amongst the other books so you’re very much delving into the intellectual and spiritual tradition in these matters and then you’re active, you’re on the front lines, you’re resisting at weapons facilities, you’re spending some time in jail. And that whole stretch through history. What did it teach you? Did you ever consider that? What did it teach you about life and life on earth?

Jim Douglass: Well if you I think if you begin falling away or you’re trying to understand signs the signs of providence, the invitations of people, the presence of God and of grace it’s going to keep leading you into deeper dimensions of truth and I keep getting surprised where I end up. But then looking back and seeing, well, that’s where it was leading all the time. For example today to be writing a book about President John F. Kennedy, I would never have imagined doing such a thing, even writing a book, actually, much less a book on this subject when I began to do writing. And I could write about the theology of non-violence. And then when I think back I’m not a historian, I’ve never studied history as a major anything of that nature and to even have the ability to write a history or investigate a crime because there’s a crime involved in this particular history. I don’t have any of the skills for that. But then I think back and realize that the thing I wrote before then which was because I had to write it was an effort to see the historical Jesus. Trying to see the historical Jesus and write about that willy nilly or learning the historical methods. I hardly had a purpose of writing about the historical Jesus to write about the historical John F. Kennedy, but that’s exactly what happened. It’s the same methods to understand either. As you’re going along God gives you what you need and the questions you need to follow.

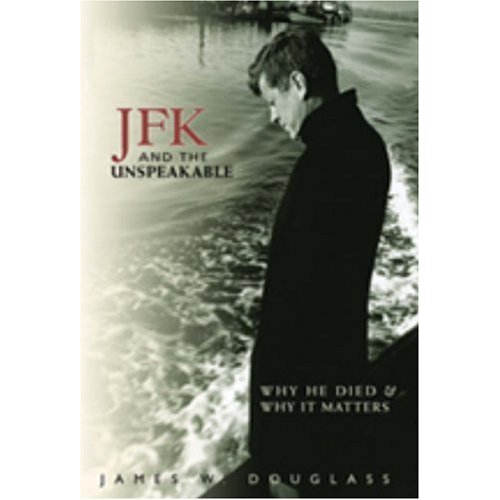

Brayton: So you spent the last twelve/fifteen years on this book JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and why it Matters. Please don’t be insulted by this question but what is your thesis? Can you tell us in the absence of having read the entire book or the readership getting this interview? What is the thesis of the book?

Jim Douglass: I don’t think I could call it a thesis but the revelation of the story which is not my story and it’s not even John F. Kennedy’s story and it’s certainly not a story that got invented by anybody is that a miracle happened. Let’s put it in another context. An event that has no good explanation in the terms in which I would ordinarily think happened. And that is that the most critical moment perhaps in history when two enemies were on the verge of total nuclear war, annihilating what we’re looking outside this window and the lives on this planet. At the worst point in that crisis they turned to each other and recognized they needed to join together and acknowledged each of them the truth in his enemy. The truth across the gulf in that instance in the Cold War between two polarized ideologies and two huge power blocks and the greatest and most destructive military forces in history. And because John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev as enemies overcame their alienation from each other and because they turned to each other in ways that I tried to describe, certainly inadequately, they had more in common from that point on with each other than either had to his own national security state. So I can find hope in Dallas, Texas where the President of the United States was assassinated because of why that happened. It happened because he was willing to die for the truth. It happened because the national security state felt it was necessary to kill him because he was a traitor. I can take hope in that event because his courage made it possible for us to sit here and hope and work and struggle for a world that continues to be there and so that all of us on this planet still have a say in it. Because he turned in the traditional, biblical, gospel sense of turning.

Brayton: So what happened November 22, 1963 according to your research? What happened on that day?

Jim Douglass: What happened was that his security was withdrawn. He was driven into a trap. He had been set up. The entire context was being controlled. Intelligence people were everywhere. All the major agencies of his government were being manipulated. Secret service, intelligence agencies, Army, the local police, the doctors were being prepared as his body was being taken from Dallas. The autopsy was being set up. The technicians for X-Rays were being prepared in such a way that it would all be lied. It would all be falsified. The lie to us as a people was already in preparation so it could be wired across the world as soon as he was assassinated. A man, Lee Harvey Oswald, who had been an operative for the CIA was ready to go in the sense that he was on his way to his own execution although it is likely that he himself had been trying to prevent President Kennedy’s assassination. All of those things were happening. In other words it was the unspeakable. Something we have not confronted to this day as a people and which is key to our understanding not only of something that went on forty-seven years ago but more significantly of something that is happening right now.

Brayton: I’ve heard you say that this is proof, this book, that the United States killed its sitting president and that is the unspeakable. Why is it unspeakable? Why can’t the truth that is coming from so many quarters, so many questions, so many obvious contradictions, why can’t it just surface? What forces are holding that from becoming fact?

Jim Douglass: The forces certainly exist in the government and the corporate world behind it. They do not want us to see the connections in a way that would allow us to understand that 1963 is right now. But perhaps also equally significantly, perhaps equally of importance is the unspeakable in us, our reluctance to go there. For example, a simple question, who paid for the assassination of John F. Kennedy? A researcher would probably sit down and say okay let’s follow the money and see if we can see if maybe it came from here or there. Once we understand the profound and overwhelming involvement of our government the answer is very simple. We did. We paid for the assassination of John F. Kennedy, we, the citizens of the United States. Our tax dollars paid for the assassination of the President. That raises a lot of questions. It raises questions about complicity, about responsibility, about what I do on April 15, what I do every day of my life in terms of giving over my power to other people to make the decisions about life or death whether it be in Afghanistan or Iraq or on the streets of Dallas when Kennedy was assassinated or across from the Lorraine Motel shot fired to kill Dr. Martin Luther King which was also paid for us, citizens of this country. We’re basically giving over those decisions to forces of the unspeakable and their unspeakable because we don’t want to recognize that it all comes back to ourselves.

Brayton: Would it be a personal collapse, annihilation of ego which is based on delusion? Is it that big, is this force so total that it is paralyzed in falsehood, refusing to see that one and on equal two? It’s has to be pretty strong, pretty deep.

Jim Douglass: It is. It is so deep that the best people in the peace and justice movement do not want to go there. It is so strong that the people we most trust that we turn on the radio to say, oh this is one program at least that I would listen to and really explore the truth. You won’t find that program going there probably when it comes to the hardest questions which includes the one we’re talking about right now, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. You won’t find that program or some of my best friends, who I respect profoundly, going there. (whom I respect. I didn’t say suspect. I do not suspect them of anything. I respect them.)

Brayton: What were you trying to accomplish? Were you trying to accomplish something? Do you want to change something about the unspeakable? Do you think there is hope that this might change the unspeakable? Do you put this in the hands of God as confessing the unspeakable? Is there any deep motive going on in you that gave fifteen years to this?

Jim Douglass: My hope is for the ability to see. My hope is for new eyes. A phrase that came when Robert Ellsberg and I were working on the introduction to the book was contemplative history. It’s not as if you study what happened to Kennedy in order to do something. In order to go out and have a new investigate of the assassination, that’s not going to work because the resources that would go into that are the sources of the assassination. That wouldn’t work. Why even do it because now that I understand what happened to Kennedy and what he did so that it wouldn’t happen to us in the sense of nuclear war I see things very differently and very hopefully. So if you go deeply enough into the darkness there’s light. Or if you reach the point where you’re going to as Gandhi said, commit yourself to an experiment in truth without reservation as to the consequences. You’re eyes are not only opened but there’s a new possibility. And the people in the other dimension who discovered nuclear power I think they went in all kinds of ways and then all of the sudden that opened up. They didn’t necessarily say I’m going to go out and discover that. If you’re trying to, as Gandhi would put it, really get to the heart of a realization of the power of truth which is the power of God, truth is God, then you have to go wherever the darkness leads you.

Brayton: So JFK, who I surmise from what you’re saying and what we’ve discussed and reading the book. That JFK was a unique President, he was a courageous President, he was a morally deep and perhaps influenced by his Christianity, he stood up to his own national security state and his generals, which is somewhat without precedent, he wanted to end the war in Vietnam, he wanted to end nuclear weapons, he wanted to end war, he was tired of war, apparently he was going to be some [reproachment] with Castro through Khrushchev, who was the enemy. What is the significance of this that he was as the President… so what? What does that mean? What does that mean for us fifty years later?

Jim Douglass: When he was President I didn’t look to John Kennedy as a source of light. Where President today, Barack Obama, who many people championed when he was running for office and they now feel totally disillusioned because he has chosen to escalate the war in Afghanistan and numerous other ways has moved in many ways that contradict the tradition they think he espoused when he was running for office. If we look into Kennedy’s history in relation to the eyes, for example, in my case when he was alive, we didn’t expect him to do what he did. We didn’t expect grace to work in that way. We didn’t think, depending on what our political allegiances were, whether we were conservative or liberal or radical, whatever we were, whether we were on the Soviet side or the American side, human beings were not expected to have the kind of grace that they did in that crisis. What I’m trying to say is that we cannot give up on Barack Obama, we cannot give up on ourselves. We cannot give up on the total transformation of race that is present in the moment. And that we can discern in ways that we will not discern unless we see how grace has happened. And grace has happened in the case of Kennedy and Khrushchev in an inconceivable degree. If we understand that we can understand that the same possibility exists right now for each of us for the vision of Dr. King for a non-violent revolution and for Barack Obama being willing to go the distance, which of course would mean Dallas for him in one form or another. We should recognize that we need to go to Memphis with Dr. King at the same time he’s going to Dallas. It’s not right to do one without the other and we need to go to Memphis as soon as possible because it’s the larger non-violent revolution that provides the context of a President to be courageous enough to give his life for peace.

Brayton: Would you agree or not that Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King, Gandhi, are not encased in evil, they have not joined something that could appear to be intrinsically evil, that is to say the United States government, the whole concept in size and history developed as it has historically, economically, is simply domination, is economic domination military given to that economic domination to protect it, to advance it, to increase it if possible. All these men, John F. Kennedy, Barack Obama, and Khrushchev are incased in something that appears to be intrinsically evil so that to change it would take a miracle and how do people who might see it that way relate to Barack Obama? Is it not simply an extension of this…

…What do we do with John Kennedy? What do we do with Barack Obama? Do we dialogue with them do we pray for them? Do we vote for them? Do we finally vote for Barack Obama or what? This is the question so I’m trying to recreate this because it’s very important for me, Jim, and I’m very interested in where you come down with this? Have I recreated it enough for a response?

Jim Douglass: Well kind of the best case analysis to even have a Barack Obama as possible person to dialogue with let’s back up a little bit and say what about Mr. Bush that preceded him. Or let’s back up further and say how about Nixon or… It’s a question that goes deeper than what might be considered the most hopeful representative of the presidency. Do we dialogue with someone in a position who we think is not going to be helpful to us and that is pervaded by the intrinsic evil of the system? Sure, why not. Gandhi would talk with him. He did – he wrote him a letter. I don’t the question is who you talk with but what you say to that person and whether it’s possible to do it both truthfully and lovingly at the same time. The question that is paramount to me in that respect is can we believe that grace can happen anywhere with anyone? I think Dorothy’s answer to that was, ‘yes’, and for Francis’ answer in terms of where he went and with whom he tried to speak, St. Francis of Assisi, I think the answer was, ‘yes’. In the Catholic Worker movement we have a tendency to be so rightly sensitive to the power…

… We may not allow grace to be there in ways that would help us.

Brayton: But why bother at all? There’s only so much time in the day. If the United States government is too evil, is too far gone, is too well developed, why give hope to that? Why not give hope to non-cooperating with that and trying to build another world at the bottom or at the middle? Why give it something when there is no real hope in it? It’s a paradox because I feel differently about Barack Obama but I still see him encased in the evil and now he’s being mangled, he’s lost control of his own image, his own story. The right wings have a story now and they’re telling the world what his story is. So you say, ‘there it is’. If we’re going to spend time as Christian non-violent people or people who follow Gandhi, Gandhi did say at the end of his life we must all stay together removed from power or politics, anyone who goes into it is contaminated. How do we not remain contaminated and how do we not go for false hope? There was a lot of energy around false hope around Barack Obama, naive, false hope, and now they’re disillusioned by the fact that he’s killing people.

Jim Douglass: But that’s distinct from dialoging with people. Gandhi didn’t have any great hope that by Nehru becoming prime minister of India things were going to go toward a non-violent future but that didn’t mean he didn’t have his friend Nehru over to dinner the next night. These are different things. You can dialogue with anyone without aspiring to a position of power or thinking that the system that person is a part of is going to make a difference. The reason you dialogue with a person is because of the person and especially if you see that the person has the hope of being way beyond the system that is all around him or her. So Gandhi’s going to have the people that are repudiating him and betraying him who were his followers. They’re still going to come to dinner. And they’re still going to ask him questions and they’re going to change their thinking even in that context because of the way he sees things. And Gandhi never ceased being a politician. At the same time as he never ceased saying that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely and seeing it going on with the people closest to him and the revolution that he was leading.

Brayton: They would come to him – he won’t go to them in terms of power structure. He won’t go to join them - to talk to them – they will go to him. They will move in his direction.

Jim Douglass: That is true but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t write to Churchill or he doesn’t stand… Many people criticize Gandhi at the end of his life because he was very persistent in going to Jinnah. He went to Jinnah and they thought well this just gives Jinnah more power because he’s waiting for you to come to him. Gandhi didn’t care how people perceived it. What he wanted to do was follow the will of God and he felt called. Of course this was at the last moment to save a unified India. The last hope was that he could get through to Jinnah which he failed to do. But he didn’t stop trying because of what his followers thought was giving power to Jinnah and he may have been wrong but that was his way.

Brayton: Did do we dialogue and pray for Barack Obama so that he becomes more non-violent, that we’re giving him a chance as a human being that we love and understand and maybe even admire so that he will have a chance to become more non-violent. Most of us did not feel that there was a chance for George Bush. My own feelings for George Bush perhaps prevented me from perhaps considering such a venture.

Jim Douglass: Well George Bush while he was in office did good things. I’m not saying that you’re wrong. I’m saying that while he was in office he did good things. And Bono in U2 managed to get him to do some good things and in other areas I think… I’m not a scholar of George Bush… I know he did good things while he was President of the United States, while at the same time he did totally horrific things like everybody else. He is different sides. He is a human being. And if you had a purpose that can somehow support or encourage or allow grace to work through you to redeem that part of that human being where he can go with it and basically because you believe in him – then do it - whether it’s George Bush or Hitler or Barack Obama or anyone in-between.

Brayton: I agree with that and I think that’s Christian non-violence. I think the temptation with Obama is that I relate to him, I think I understand him in a way that I perhaps didn’t understand Reagan or Bush or Bush first or Bush second or Nixon and maybe that’s self-righteous too but maybe that’s what got the energy going for Barack Obama. That the middle left could relate to this guy. He spoke their language. Therefore I think that we can get him to be more in the Kennedy mode because Kennedy was like that too.

Jim Douglass: But recognize that if he were to do that, that’s the end of Barack Obama as the President of the United States. It’s the beginning of Barack Obama as a transforming vision.

Brayton: And that’s why some people say and I think it’s very true along those lines that the best thing he could have done was be a four year President. Get in there and say tell the truth for four years and if he absolutely did something they could impeach him on let them impeach him.

Jim Douglass: Well, yeah, he would be less than a four year President.

Brayton: But to try to be an eight year President would be a mistake. So, what’s next? Is there anything next that you would like to tell us about in terms of a book or an idea or a campaign or are your hands full with doing JFK and the Unspeakable?

Jim Douglass: I’m finished doing that. I have a book, a story, of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King to complete and in order to do that I found I had to write the story of Gandhi’s assassination, so that’s what I’m working on now.

Brayton: Good – well, thank you for all you do and all you continue to do. And stay healthy and clear headed. That’s what it all takes if you’re going to spend all these years on it.

Jim Douglass: Thank you, Brayton.